I'm getting my arm operated on today to correct some nerve compression noise in my arm. I thought I'd have the time to stockpile some posts before today, but I didn't have the time. More posts when I've two hands again.

Anyway, I'd like to post on something comic fans often have difficulty understanding and/or accepting: the application of trademark law and copyright law to comic books. This was originally written as an explanation of the reason why DC can't print a comic book with "Captain Marvel" in the title, so it may come of a little Cap heavy.

***********************************************************

I, too, used to think that copyright and trademark were related bodies of law, They have some concepts in common, like infringement and fair use, but the reasons the laws in these areas come from two different

schools of thought.

Copyright law may be considered as a reward for an author. We'll use "author" throughout this discussion as it is the term used in the U.S. Copyright Act. However, any work with a minimal amount of creativity that is fixed in a tangible medium, may be copyrighted. Books, scripts, musical composition, film, comic books, and sculpture are all examples of copyrightable material, thus a sculptor is an "author" for copyright purposes.

Copyright was, once, exactly that, a right to make copies. An author, and only an author, had the right and to determine when and by whom copies of her work would be made and disseminated to the public (unless the work was created under a work-for-hire contract). Over time, other rights became included in the copyright so that it is less a right to copy and more a bundle of rights that an author is free to use as she pleases.

The U.S. Trademark Act (often called the Lanham Act after the person who introduced the bill into Congress) was enacted as consumer protection law, not to protect the owner of the trademark, though that the owner does benefit cannot be denied. The concept of a trademark was created as soon as there two people creating a similar product for consumer consumption.

An example: Quintus Flavius and Marcus Hermanicus are both producing wine in Rome in the third century, BCE. To let taverns know/remember which wine is his, Flavius marks the wine casks with a bunch of grapes. This mark acts an identifier of a product's source, thence as an indicator of quality for a consumer and tavern owners come to know that a cask marked with bunch of grapes will generally be a good source of wine. Hermanicus sees his orders decrease, so he begins marking his casks with a similar mark, causing some people to buy his wine, only find it to be an inferior product. Because of Hermanicus's action, Flavius has lost sales and lost goodwill with customers who think that the quality of his product has fallen.

Modern trademark law is in place to prevent this kind of thing. At its most basic, trademark law is in place to prevent a party from using the same or similar trademark of a competitor on the same or similar product the competitor produces.

Before continuing, I should highlight two points:

First, copyright law (and patent law) is entirely under the control of the federal government, that power granted to Congress through the Constitution (Art. 1, sec. 8. cl. 8). Trademark law was left by default to the states to create and enforce as they saw fit. In that time, that made sense since anything a tradesman produced would

probably not move out of the state, let alone out of the county where it was produced. The Industrial Revolution changed how products were produced and transported, however, and the federal government saw how federal control of trademarks could be helpful. However, the first federal trademark act was based upon the copyright and patent clause and the U.S. Supreme Court found that an improper use of federal power. Eventually, a federal trademark act would be passed (more properly based on the Commerce Clause of the Constitution (Art. 1,

sec. 8. cl. 3) in 1881. The Lanham Act would be enacted in 1946, but the trademark law of the individual states may also apply when a mark is used improperly. In fact, if a person creating a product has no desire or intent to market that product across state lines, there is no reason to apply for a federal trademark since the law of the state that person lives should theoretically be adequate.

Second, it should be remembered that there have been major additions or overhauls to the U.S. Copyright Act (U.S. Code Title 17) and Lanham Act (U.S. Code Title 5, Chapter 22) since both were enacted. For instance, when Whiz Comics was being published, the form of copyright law that was applied was derived from the Copyright Act of 1909. This was a much stricter act with regard to how a copyright was obtained and maintained; I honestly don't think that all the Fawcett material that Bill Black reprints would not be in the public

domain and we could have had a Bulletman or Spy Smasher Archive bynow. Events that DC brought up during the Fawcett case to show that Fawcett had let its copyright on the works featuring Captain Marvel become invalid would not even be an issue any more (and were becoming less important in the years after the court case any way).

A simple way to remember what copyright protects and what trademark protects is this: Copyright protects creativity, trademark protects consumers.

The word SUPERBOY cannot be copyrighted in and of itself, the copyright office would deny the registration because the federal rules prohibit the registering of a copyright for:

"Words and short phrases such as names, titles, and slogans; familiar symbols or designs; mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering or coloring; mere listing of ingredients or contents." 37 C.F.R. § 202.1(a)

However, SUPERBOY is exactly the kind of thing that is meant to be trademarked. It is a word that has no inherent meaning. To put SUPERBOY on the cover of a magazine, i.e. to trademark SUPERBOY for a comic book title is perfectly legitimate. There doesn't even have to be anything to do with a "superboy" within the pages of the magazine, since a knowledgeable consumer understands what SUPERBOY means with regard to magazines (or will, if the magazine has yet to be produced). The converse of this is that the entire contents of a SUPERBOY magazine from front cove to the back cover is suitable for copyright protection. It is a creative work. No matter how banal the writer's dialog or how poor the artist's attempt at perspective, it is still something that someone (or someones) created, something that didn't exist previously. The threshold of creativity is a very, very low bar and courts have gone out of their way to explain that it is not their job to pass judgment to determine if a work is creative "enough" (ignoring for now the issue of the whole of a person's creativity being copying the work of another).

To slightly complicate matters, if DC wanted to take an isolated drawing of Superboy from the comic and use it as a corner logo (like Marvel and DC used to do through the seventies) for the SUPERBOY magazine, that drawing could be registered for a federal trademark. Yes, the artist created the drawing, but just like MR. PEANUT or TONY THE TIGER, a creative work can rightly serve as a trademark and, unlike a copyrighted work, the trademark will never enter the public domain so long as the owner properly maintains its registry. (Of course, copyrighted works entering the public domain may be a moot point, but that is not the subject of this post.)

What does that mean in the big picture? Well, anyone can write a story featuring a character named "Captain Marvel." Anyone can wrote a story featuring two characters named "Billy Batson" and "Mary Batson." However, if you write a story featuring a characters named "Billy Batson" who turns into a character named "Captain Marvel" (or even into a character who goes unnamed that has powers similar to Cap) well, there you got yourself a possibility of a lawsuit for copyright infringement.

This doesn't mean that you can't write a story featuring a person who says a magic word to become a super-hero. There are stock situations and ideas in any genre that are available for use; those can't be copyrighted. However, copyright becomes available when a writer had creative touches to the work that differentiates it from any other of that type.

That being said, Marvel would not have needed to secure permission from anyone to create a character named "Captain Marvel." Anyone can so long as that character doesn't infringe upon the other versions of characters similarly named. However, because Marvel owns the trademark for MARVEL, and CAPTAIN MARVEL, no one can use those words in the title for a comic book.

If you do a search at the PTO website, http://www.pto.gov, for Superman, for instance, you'll find that DC has registered the name as the title of a comic book, as well as for a variety of products from underwear to coloring books. This registration prevents anyone else from creating a Superman coloring book. If someone were to create a Superman coloring book, that would be trademark infringement for the unauthorized use of the trademark. If the coloring book were to use images of Superman on the cover and/or in drawings inside, that would be copyright infringement, because a derivative work was created without DC's permission.

(As an aside, and before someone brings it up, let's tackle the Fleischer Superman cartoons. How, you ask, even if the cartoons are in the public domain, can those be put out on DVD and use DC's trademark, SUPERMAN? This is because federal law allows a person who is making available public domain to tell consumers what she is selling. So, the producer is allowed to put "Superman" on the front and to use images of the character taken from the cartoons itself. (However, if the producer were to create new images of Superman and puts them on the box, that would be an act of copyright infringement. Similarly, because of the new images are being used under the SUPERMAN trademark, DC could assert that the producer is also infringing on its trademark as the producer is trying to pass off unauthorized material under DC's trademark.)

When Fawcett pulled out of the comic book business, two things happened that is still affecting comic books, I am ignoring the transfer of certain properties to Dell. My comments are based solely on Fawcett taking care of its own properties and I don't need to complicate a complicated topic more.

First, Fawcett did not renew the copyrights on the comics it had published. Had Fawcett done so, none of the stories being published by Bill Black would be available in the public domain and I'd have that Mr. Scarlet Archive by now. (My belief is that because the Fawcett stories are in the public domain, DC will never publish any collection of those works beyond Cap because all DC would be doing would be cleaning up art and making it

available for anyone to reprint and resell. Despite what Bill Black would have you believe/would like people to believe, the slight alteration of a comic page may identify is as coming from Men of Mystery, but I just don't think that if brought to court the alterations would be enough to give Black a copyright on matter in the

public domain. It goes against the public interest to take something back from the public domain after it has entered it.)

Second, Fawcett did not renew the trademarks for their comic books and that is understandable since Fawcett wanted out of the business. Apart from paying a fee, a federal trademark must be shown to be in actual use in commerce if it is going to be granted that renewal. IMO, this is why every so often DC will publish a new "The Brave and the Bold" mini-series or an All-American Comics one-shot. By doing that, it keeps the trademark active and out of the public domain.

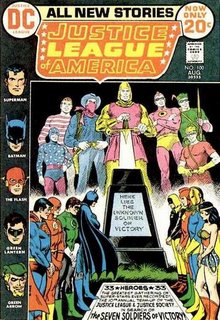

Regarding Marvel and Captain Marvel, the simplest explanation is that Marvel swooped in when it found that the trademark for CAPTAIN MARVEL ADVENTURES had expired and published its own Captain Marvel comic book, thereby securing the trademark. As is well known, this is why DC produced ashcan issues of comics titled SUPERBOY, SUPERWOMAN, and SUPERMAN COMICS, and Fawcett THRILL COMICS and NICKEL COMICS without regard for the contents. The companies needed to show that they had a magazine on sale in commerce to secure the associated trademark.

(If you've been paying attention, you may have seen that the publication of ashcans skirted the letter of the law at the time. To obtain federal registration of a trademark, the mark had to have been in use in commerce, that is, for sale across state lines. An ashcan edition was lucky to have made it out of a company filing cabinet, let alone onto a news stand in New Jersey. Things tightened up in the intervening years, so that Marvel had to actually produce a MS. MARVEL comic book to lock-up the trademark, for instance.)

Trademarks serve as indicators of quality for consumers and MARVEL has a certain meaning to consumers of comic books. In the early fifties, MARVEL could rightly be associated with Fawcett super hero comics, but by the time Marvel applied for registration of "Marvel Comics Group" Fawcett's Captain Marvel was off of the radar of the average comic buyer so MARVEL on the cover of a comic book in 1974 was an indicator of a different kind of product than it had indicated in 1954. I offer that Marvel may not have even thought that CAPTAIN MARVEL was available until M.F. Enterprise's version of Captain Marvel come out in 1966. When that version ceased publication within a year, Marvel probably felt it should sew-up control of that name since if one rival used it, what could stop the Distinguished Competition from now printing a comic with that title? (Marvel's first use of Captain Marvel was in Marvel Super-Heroes #12, Dec. 1967.)

So, there you have every reason why DC can publish comic books featuring Captain Marvel, but will never be able to use the character's name on the cover of any of its comics. Not only does Marvel own MARVEL for use with comic books in general, it also owns the trademark CAPTAIN MARVEL for comic magazines. In summary:

1. Names cannot be copyrighted, Any name may be used by any author at any time. However, if you plan on calling your character "Batman," he damn well better not resemble any variation of the character ever published by DC or else you could be hauled in on a copyright infringement allegation.

2. Marvel did not need to secure the permission of anyone to create a character named "Captain Marvel."

3. Titles of periodicals may be trademarked.

4. For a trademark to remain valid, it must be maintained which requires an occasional payment and use in commerce. When Fawcett stopped publishing "Captain Marvel Adventures," it really couldn't protect the trademark because it couldn't publish Captain Marvel anymore. The trademark fell into the public domain and anyone who wanted to could publish a comic book with that title.

5. When use of the name became clear (that is, neither Fawcett nor M.F. Enterprises held the trademark on the name for a comic book), Marvel published Marvel Super-Heroes #12 cover featuring Captain Marvel. That began the process of its securing CAPTAIN MARVEL for its exclusive use as a trademark for a comic book.

6. Because Marvel owns that trademark for use on a comic book, DC cannot use the name of Captain Marvel on the cover of its comics. To do so would infringe on Marvel's trademarked name. This created the situation that people think "Shazam" is the name of the Big Red Cheese.

7. If Marvel hadn't secured the use of "Captain Marvel" as a trademark, DC could have. However, because Marvel owns MARVEL, and thereby the exclusive use of it on comic book covers, DC would still have been fighting an uphill battle. This makes DC's use of "Shazam" as the trademark associated with the original Cap more understandable: there is nothing to prevent DC (or Dark Horse or Image) from using a character in its comics named "Captain Marvel," but there is plenty to prevent any of those companies from using "Marvel" on its covers.

If you still have questions, send me an e-mail or post it here. I'll answer as soon as my arm lets me.